Subject: Introducing you to my Zettelkasten

Dear Friend,

I wish you a happy, productive (& lucky) New Year! I am certain that I will have a lucky one because I won the flouri in the Vasilopita.

What’s that, you ask?

The Vasilopita is a delicious bread-like cake that is traditionally made and eaten by Greeks on New Year’s Day. But it’s not just about the tasty treat—there’s also a special custom associated with it.

As the Vasilopita is baked, a coin is randomly placed inside the dough. When it’s time to cut the cake, everyone gathers around with excitement and anticipation. As each person takes a slice, they hold their breath and hope that they will be the lucky one to find the hidden coin in their piece.

Finding the coin is thought to bring good fortune, love, and health to the lucky recipient for the entire year. It’s a fun and festive tradition that adds a little bit of magic to the start of the new year.

So if you’re ever in Greece (or around Greeks abroad) on New Year’s Day, be sure to try a slice of Vasilopita—and who knows, maybe you’ll be the one to find the lucky coin!

Well, for the first time in years, I was finally that lucky one to pick the piece that contained the coin, and so, naturally, I now have high expectations for 2023!

Of course, I won’t stay passive and expect the luck to pour in. I have great goals for this year—many of whom involve my Zettelkasten.

And this is why I am writing to you today (although I also wanted to boast about the coin).

In my last letter to you, I promised that I will introduce you to my setup and dive into Scott’s book.

So, that’s what we are going to do.

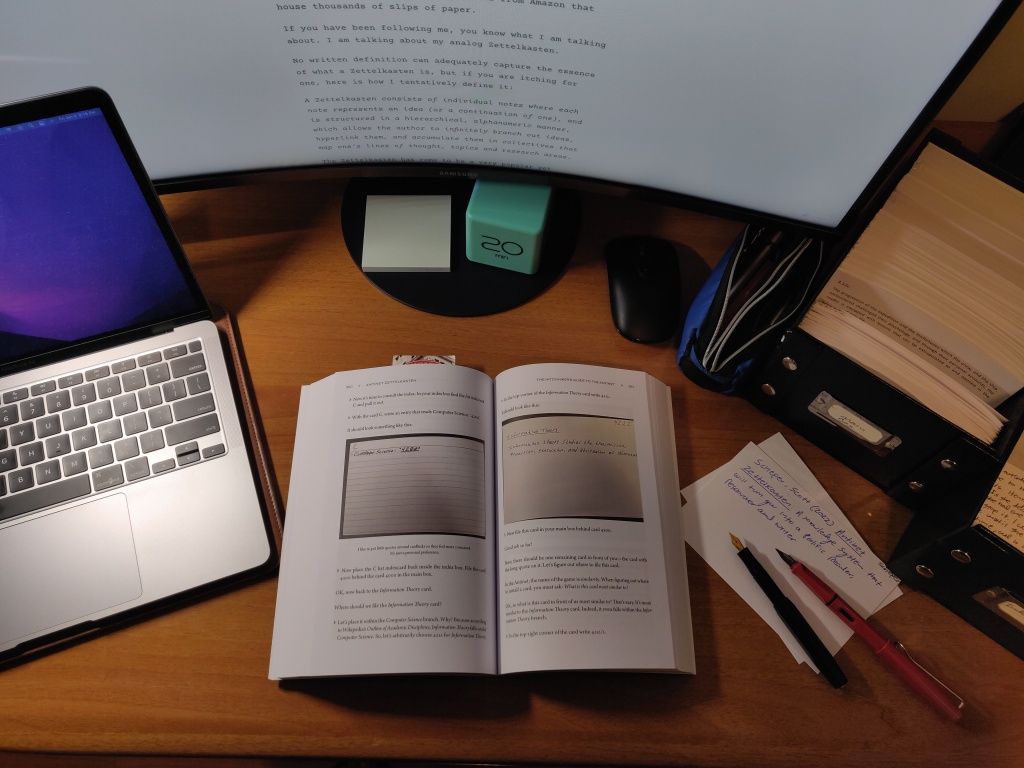

First, here is my humble, and quite crowded desk, where I spend the bulk of my days reading and writing:

Did you see it? On the right of the picture? That’s my humble Zettelkasten—my mighty conversation and research partner, consisting of two cheap storage boxes from Amazon and hundreds of note-cards.

Let’s take a closer look.

This is my main box where research is stored and insights are born.

If you are familiar with Scott Scheper’s Antinet, whose numeric-alpha scheme is inspired by Wikipedia’s outline of academic disciplines, you will find my convention unfamiliar but not strange. I was introduced to the Zettelkasten method a few years before I found out about Scott’s Antinet implementation, and so I have adopted Niklas Luhmann’s naming convention and top-level category philosophy. As such, my note IDs start from 1 and ascend to infinity (theoretically). Also, I tend to use fewer slashes ‘/’ to branch my notes, instead opting to alternate letters and numbers (e.g.,2/1ab1c3) in the Luhmannian way.

Now, let’s take a look at few notes that reside around the ‘1’ top-level category, which was structured around the topic of Global Studies. I say ‘was’ because I believe that my top-level categories are largely arbitrary. Simply, they are starting points that, over time, branch out (or in—depends how you see it) and establish new topics that no longer fall under the umbrella of Global Studies. And that’s OK. This is what Scott refers to as “fuzzy categories.”

To elaborate how my Global Studies category has become fuzzy over time, consider the themes within that section:

1.0 GLOBAL STUDIES

- 1.1 THE GLOBAL NOVEL

- 1.2 WAR

- 1.2A MEDICINE IN WAR

- 1.2/4 STIMULANTS

- 1.2/4a1c HISTORY OF ADHD

- 1.2/4 STIMULANTS

- 1.2A MEDICINE IN WAR

As you can see, the history of ADHD has, at first glance, nothing in common with the area of global studies—yet, gradually, my research interests meandered to that direction. Since then, that section has grown even more to encompass contemporary treatments of the disorder and the ways through which pop culture lowers our collective attention spans.

I know that sounds dense and complicated, especially for those of you who are new to my newsletter. All you need to understand is that a Zettelkasten doesn’t function like a folder structure. Categories are simply starting points for your thoughts and knowledge. Ultimately, what matters is being able to identify the information in the file, create connections with other notes, and resurface that information by using your index.

Now, before I show you my index, I want to address Luhmann’s collections and the compromise I came up with when I was conceptualizing my own Zettelkasten structure.

First, it’s important to know that Luhmann’s file was divided into two collections. The first collection (1951-1962) incorporated topics in law, public administration, political science, philosophy, sociology, etc., and included 23,000 notes divided over 108 sections. The second collection (1963-1997) included just 11 top-level categories and hundreds of subsections, totaling 67,000 notes.

The fact that, in his second Zettelkasten, he only employed 11 top-level sections, or topics of inquiry, demonstrates a problem-solving approach whose focus was cross-topic connections and not rigid categorization (the content quickly merged and branched out becoming fuzzy and radically different from the starting category).

It is the second collection’s functionality and promise as a system, that enables serendipity, which has thrust Luhmann into the spotlight in the recent years. Now, when Luhmann was starting his second Zettelkasten, he had a clear goal in mind: drafting his theory of society. I had no such interest with my Zettelkasten. My initial goal was to use it to expand my knowledge of niche areas and embrace life-long learning.

To do that, I figured that it would be more advantageous to create a common ground between Luhmann’s two collections so that I can pursue my generalist interests and expand my niche expertise without the need for two different boxes.

So, instead of resorting to creating 108 categories, I have decided to expand inwards in my file. This way, in the long run, knowledge will be tightly intertwined together—resembling Luhmann’s second Zettelkasten—rather than spreading it across highly specific sections that risk rendering linking and referencing cumbersome and inefficient.

Finally, let’s tame all that chaos!

Introducing the index.

The index is the tool that allows you to navigate and make sense of your Zettelkasten. It tames the chaos of references and the increasingly diverging topics in you file.

Keep in mind, however, that the index doesn’t aim to capture the entirety of the file, for it is not conceived of as a table of contents. Its main goal is to provide entry points to your notes so that ideas and topics can be located more efficiently. The index also aims to accomplish thematic completeness. Keywords are chosen wisely and strategically. Luhmann had determined that they should be purposefully broad and contextual so that a search for a specific term or a line of thought would uncover other potential paths and clusters of ideas that he could take advantage of, and which could provide fresh insights and new inquiries.

Lastly, no matter how complicated everything sounds, in essence the principles are simple, especially when you internalize the following:

You can try to organize your Zettelkasten, attempt to tame it, but your imposed structure will always elude you. To maintain a Zettelkasten means to accept a degree of chaos, for it is in the blur where ideas link and evolve.

That is all for this week.

It turned out to be more complex than I had planned, but no need to worry. I simply wanted to establish the foundational thinking behind my own method and set the stage for next week’s letter (which will be shorter) and will focus more on the Antinet’s mechanics.

I hope this has shown you the amazing potential and versatility of the Zettelkasten and some approaches you can take to personalize the method. There’s no wrong way to create a system that works for you!

Sincerely,

Nikos Panaousis

P.S. Keep in mind that in my day-to-day life, I do not allow such complexities to disrupt my process, which is pretty straightforward: write notes, install them in the file, create links where needed, and maintain an up-to-date index. The philosophical ambiguity is useful only in the beginning stages or when explaining the method to others. In the end of the day, your Zettelkasten is just a trusty conversation partner.

Leave a comment